Episode #425

Sarah Marshall is the co-creator and host of the award-winning podcast, You’re Wrong About, Podcast of the Year at the 2022 I Heart Radio Podcast Awards. You’re Wrong About revisits what we think we know about history and cultural events that have lodged themselves into our brains, and how that compares with what actually happened. Marshall sat down with me to talk about how she got into podcasting in the first place, why she and co-creator Michael Hobbes started a Patreon a year later, what it’s like identifying more as a talker now than a writer, and what she has learned while touring her podcast with comedian Jamie Loftus. I also might have learned just what I’ve been getting wrong about both podcasts and comedy?!? We definitely learn how Sarah Marshall feels about the movie Forgetting Sarah Marshall.

Want to discover other cool Substacks? Each morning, The Sample sends you one article from a random blog or newsletter that matches up with your interests. When you get one you like, you can subscribe to the writer with one click. Sign up here.

If you’re not already subscribed to my podcast, please seek it out and subscribe to Last Things First on the podcast platform of your choice! Among them: Apple Podcasts; Spotify; Stitcher; Amazon Music/Audible; iHeartRadio; Player.FM; and my original hosting platform, Libsyn.

This transcript has been edited and condensed only slightly for your convenience.

You seem like a kindred spirit to me. We’re both journalists who have been slightly sidetracked by our side hustle.

The hustle, I guess reaches out and grabs you, and pulls you in an alley and you’re like, Oh, I like it. Yeah.

Oh, I think this is the real thing.

Yeah, yeah!

It turns out I’m a talker, and not just a writer. And then also, apologies in advance for asking this question. And sounding like my mom. Not that you know my mom. So apologies to my mom for even bringing her into this, but for my first question: How is your book on Satanic Panic coming along?

I know your mom because she’s my mom. I mean, the answer to that is that the pandemic hit, and then I was like, Oh, my brain is going through some changes. As so many of us did, I think, and I really forgot how to read and write for a while, you know, or like, technically I knew, but it was just like, it was like trying to thread a needle with no depth perception. You’re just like, well, I feel like I should know how to do this. And yet here I am unable to do it. And I feel like only last fall that I really started writing again, and write an essay that ended up published in The Believer that kind was a project that I started and able to finish. and so I feel like it’s unfortunately been contingent on my ability to come back to my writing self, but I feel like that’s the part of the process that I’m in and I’m really enjoying it because it is like, I don’t know, I think there’s also you can work the words as I think you can work with anything just like too much, and then at a certain point, it’s like very difficult to see them for what they are and you have to kind of, I don’t know. I’m at this point, a big advocate of taking a break from the thing you built your identity around. It probably would help.

So I should probably just end this podcast now, and start something else.

And then we took a walk. I mean, it is something that’s still on the horizon for me, but it was such a process of trying to force something that isn’t available to you. At a certain point, I think you just have to concede that process is happening and you have to be patient with it.

Full disclosure, I think I might have said the words to my parents: ‘I want to write a book about comedy’ in 2010. And we are talking right now in April of 2023. So who knows when I’ll actually finish this book. When you’re listening in the future. Both of us will have written this book, but Satanic Panic was the first episode of you’re wrong about back in May of 2018. But that’s not your origin story. I know another thing you wrote about for The Believer back in 2014 about Tonya Harding — that is the origin story for the podcast, right?

Yeah, yes. Because Michael Hobbes, who founded the podcast with me and whose idea it was and his initiative. You know, this initially is all because he was writing for HuffPo at the time.

HuffPo stands for The Huffington Post, which used to be a popular website.

Yes, famously. I started writing, publishing online in like 2012 and at the time, like, there were viral articles, which I know that still happens to an extent, but that was the era of like, Yeah, I’m just gonna set up a website where we pay ordinary women criminally-low amounts of money to talk about the most fucked up big thing they’ve ever done in a parking lot. And that was a business model that worked for a while, which is now very quaint, because like, now you have to, you know, be lip synching to Megan Trainor.

But yeah, so Mike initially reached out to me because I published the Tonya Harding article in 2014. That was the first thing I’d published that really felt like people I didn’t know were reading, and it was the result of like many years of kind of impassioned bar speeches for me, and so Mike read it and really loved it. He sent me this anonymous note on Tumblr, which I remember receiving and I remember it really touched me. And there was no way to get in touch with him, and then he reached out in 2016 because he was at HuffPo then, said: ‘I like your writing. You should submit.’ And yet I never had an idea normal enough for them. But I knew that I liked his writing as well. And we were in touch and so when he had an idea to do a podcast revisiting this remembered history in early 2018, I was the person that he reached out to about that. Which, I was just like, yes!

But I imagine Tonya Harding probably wasn’t the first news story or subject that really annoyed or like percolated in your brain. Do you remember what the first moment when you you realize that everything you were being told was wrong?

Wow. Wow! I mean, OK, this is like the first thing that comes to mind, which is ridiculous, but I feel like does demonstrate something. When I was I think in third grade we all there was a day where our teachers were like, ‘Alright, we’re going to the computer lab and you’re all going to write a letter to Socks the cat. The Clintons’ cat. And I remember just being like, ‘This is insane! This cat’s not going to read these letters. Why are we doing this?’ And then actually recently, I was like looking, I forget what for, but I found this book that was like Letters to Socks. America’s Children Write Letters for the Clinton Cat (close! Amazon link) and I was like, oh, that’s why we were doing that. It wasn’t because it was purely in an experiment in wasting our time as children. It was because our teachers wanted to be part of this equally meaningless press release type thing. And like, I don’t know, I remember just like as a kid, these moments where adults would just be like, you have to do this thing. It’s very important that you do it everyone write a letter to Socks the cat. And like, so much of it metaphorically was like also writing a letter to socks the cat. Because cats don’t read, famously. The only time they show an interest in literature is when they want to stand on a book you’re reading so they can show you their little butts. And also, even if Socks could read. Think about the amount of mail he’s receiving. There’s no point. And just like this feeling in the 90s growing up that adults, most of the stuff they were working really hard to make sure that we did was already clearly a waste of time. And how that makes you doubt everything else they’re talking about.

That Socks book was light years before Tumblr. Because when I think of Tumblr, I think about the period, especially with respect to comedians, where they were getting books published, but all of their books were crowd-sourced. Much like the Socks thing where it’s like, they set up a Tumblr that had this theme, but everything on the Tumblr was contributed by other people.

Right. It was this exercise to generate content for the sitting president.

And you see no royalties or anything from it.

Come on, it’s a raw deal for the kids.

And then the other thing your Socks story reminds me of — so many of the early episodes of You’re Wrong About cover these things that, whether you’re Gen X or millennial, you grew up hearing these stories or urban legends, and we just all kind of latched on to them. At some point, they just became fact, and not debatable.

The reasons that people latch on to the things that they do are always so fascinating, in terms of our lifetime pursuits, and I still remember the feeling of being a kid who like, you felt like you knew what the truth was, but you were absolutely powerless to get anyone to listen to you about it. Whether it was like parents, teachers, other kids who were sure of their own ideas. And certainly as a kid, like I had my own share of arrogance about stuff, because that’s one of the things that keeps kids alive because they don’t have a lot else going for them, survival-wise. But yeah, I guess the feeling like I think the universal feeling of childhood in America, where it’s like, you know, inevitably, I think way more than people are willing to hear about and what do you do with that? And how frustrated do you choose to still feel about it in adulthood?

One of those urban legends, speaking of comedy purposes, I got involved in comedy professionally in the mid-90s when I was living in Seattle, but even back then I remember being fascinated one by how many comedians just casually dropped a Richard Gere gerbil reference, joke.

Yeah.

But then it really stuck in my head and I was like, somebody started that.

Yeah!

It came from somewhere. Someone was the first person to send this idea out into the world and then it just grew a mind of its own.

Yeah. And that is like that. Those things are so fascinating, right? Because it’s like it was always Richard Gere. And I also feel like culture kind of coalesces around these things where it’s like, because if you make that joke, right? And if people laugh at it, like, are they laughing at it because it’s funny? Or are they laughing at it because that’s their way of saying I remember? I know the thing you’re saying! We’re all together and we all know it.

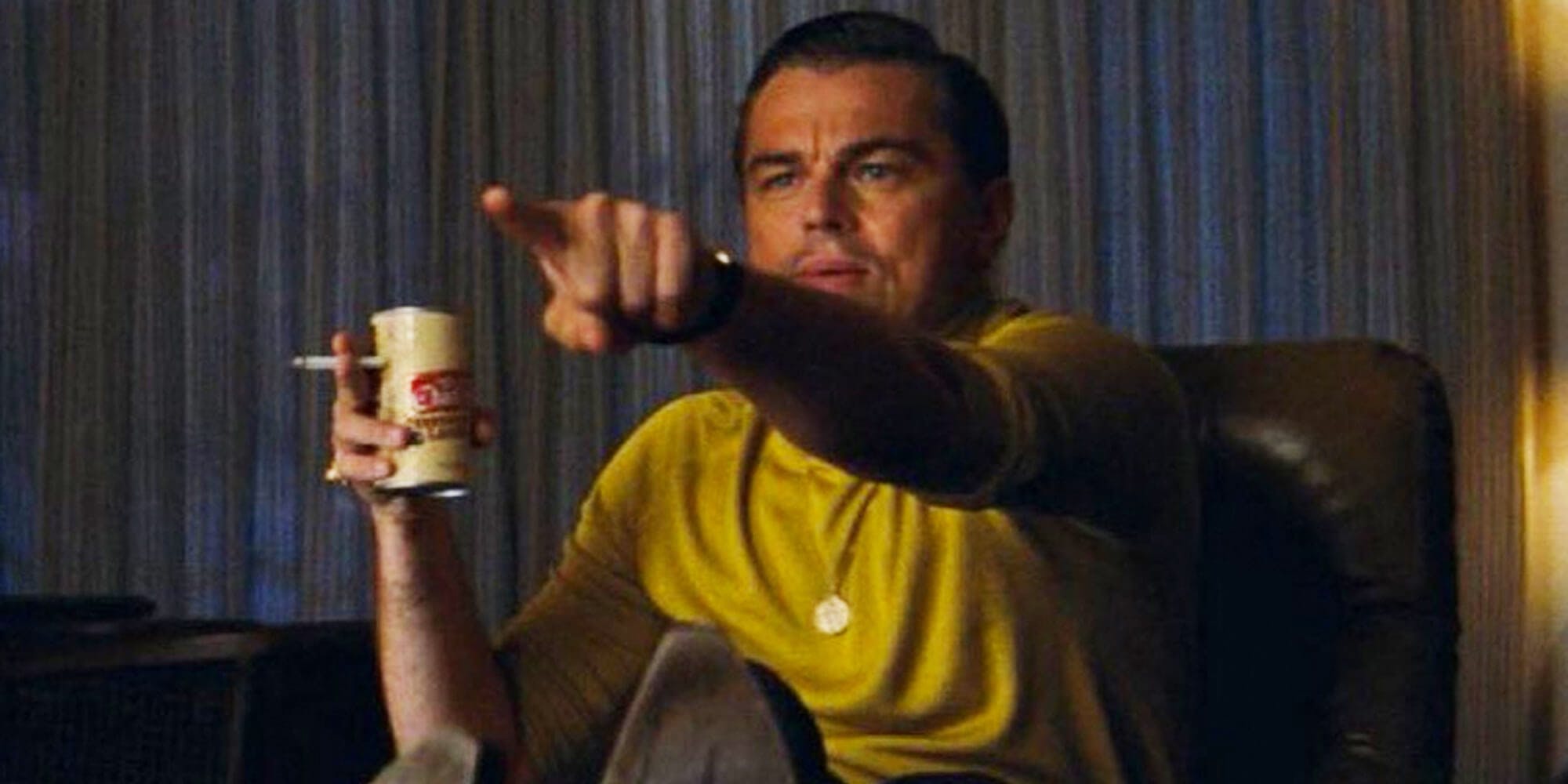

Right. How much of comedy is just nostalgia and reference points? Or that meme of Leonardo DiCaprio pointing at the screen.

Yeah, when I saw that movie, it was a couple years after that meme came out. And then I did the meme. It was a real moment.

When you wrote the piece for Believer about Tonya Harding, you were teaching at Portland State University. What were you teaching?

I was teaching composition. Which was fascinating because we had I don’t know what the levels are now or if they’re the same, but we had, there was like Writing 121, which was the basic, the freshmen are in a track where they have to take a writing class, but that’s what they take. Writing 222, which was the research paper. And then Writing 323, and you would get assigned to that and you’ll be like, what’s 323? And they’re like, I don’t know! I don’t know, figure it out. It’s something. Nobody knew what 323 was. You would get in there and wing it. And I feel like you know, this is not the endorsement academia probably wants, but like, if you want to work directly with college students with no supervision and also get paid like a quarter an hour, then you should be a graduate student teaching assistant, or an adjunct, because my title was grad assistant. You might imagine that means that a professor teaches and you kind of watch them and then you grade their papers. But no. They’re like, you’re 22, you’re gonna teach a bunch of college students who you were very recently one of how to do the thing that many people most fear in the world. So just yeah, have fun with that. And to me, the constant challenge and the thing I most wanted, and found most elusive was just like, generating conversation and getting people to talk to each other. I was one of those hippies who made people sit in a circle.

Especially coming from where you are now as a journalist who’s questioning everything. As a teacher, did you question the curriculum? Or did you teach by the book?

I’m sure I had by-the-book moments, but it also helps that it was a writing class. So you ask people like how to teach writing and they’re like, uhhhh? Hard to say. It’s not like chemistry, I think where you can be like, well, of course first, you know, memorize the elements and then do, I don’t know how chemistry works.

There’s a table. There’s a whole table.

The whole table. There’s a table, and then presumably other furniture as well. Writing feels special to me, because it’s something that like, people who have done it for their entire lives, people who have won like a Nobel Prize for doing it, you ask them about their writing process, and they’re like, Ah, oh my God. Don’t talk to me about that. I don’t know. And so I was very of the mindset of like, I just want to create a situation where people are talking and communicating. I did a lot of current events. I did a lot of stuff that I feel like even now would be more fraught, but it was like 2011-2012-2013 We talked about election stuff. We talked about politics, we talked about — I spent a lot of time teaching ads and sort of how to recognize logical fallacies and like bad arguments being made to try to appeal to you. So yeah, I mean, I feel like a lot of the roots of the show were in teaching because I was trying to — I was like, well look, if I have four hours of your time every week and I honestly don’t know that much about grammar, then maybe the best I can do is show you how to use language but also show you how it’s being used on you, all day long every day of your life and how the reason that you want to get better at using it, is because that’s how our modern wars are waged.

Right? I mean, even just in the five years since you started You’re Wrong About, the whole notion of propaganda has spawned this even worse form, thanks to social media, and how people have figured out how to weaponize it. It feels like we’re wrong about so many more things than we were five years ago.

Yeah, and I wonder about that. I thought a lot about, like, at the start of the pandemic, I was like, maybe germ theory was just like a blip on human consciousness, right? Because you think of people as like, we learned how germs and infection worked. And then we were like, great, now we understand diseases. And then it’s like, in reality clearly, like a lot of people never quite took to that. And, yeah, this thought of like, I don’t know, like the last couple hundred years I think have been really weird for humans, because we are, by nature, in many ways, very superstitious, very prone to ritual, very prone to magical thinking. And now it’s like, I think technologically we have, like if we were, if you and I were around in the Renaissance, I feel like we would really be governed, our sense of how the world works would be governed in many ways by how we feel it works or how like, you know, some, white guy with a court position feels things work, and then it would be like great! How we feel is what is true and there is a guy who’s saying that planets revolve around the Sun but they burned him to death so we’re fine.

We probably also have have a lot of things wrong about Renaissance fairs. That’s a separate podcast. That’s your podcast. That’s not mine. I noticed there’s a Patreon for it that was started the year after the podcast launched. What was that first year like when it was still just, you and Michael in the wild?

In the wild? Yeah, we were both supporting ourselves through writing. And also I was in my sort of freelance housesitter days. I would be like, what’s that? You’re going to Europe for a month? You need someone to feed your goats in a tiny town in upstate New York? Yes, please. Really in retrospect, it was like a self-created kind of artist residency thing, where all these things that you apply for, and are taught, are going to be a part of your life, and sort of writing school. You apply, and you get chosen to go to a weird house and work on your project, and I just found other weird houses that were available to normal people. And so yeah, and it’s funny to look back on now, because when we started doing the Patreon, and we started. We had a bunch of people sign up on the first day and they were really excited to do it. I clearly have issues with like, valuing my work because I had this like recurring mental image of like, literally being arrested for fraud because I had like tricked people into thinking they liked my podcast, but it wasn’t sufficiently good that they actually should like it, and I was like fooling everybody. So that’s kinda wild.

Was that the point though, at which you realized that the podcast could be the main thing and you could put everything else on the backburner? Or what was the moment when you realize, oh, this is the thing?

I think I realized it later than everybody else, and I think it was really, in the pandemic when we started you know, in 2020, we made more episodes than we ever had before or will, because we were doing like two a week. And that was just like, what there was room in my brain for, and how I was sort of showing up as a human being in that time. Identity is a funny thing. Like I’m obsessed with the fact that Barbra Streisand, according to a very recent interview, she was like, Oh, I don’t think of myself as a singer. I think of myself as a director and an actor who sings and it’s like, OK, but Barbara, No. That’s nice that you think that but like nobody else, no one else thinks that. No one’s like, oh, yes, Barbra Streisand, the director. But it’s like, I don’t know. I feel like maybe there’s a tendency that I at least see in myself and Barbra Streisand to identify as the thing that it is harder to be. And what I think I love about doing this podcast and podcasts generally is that like, I don’t know, I think there’s because like people have different skill sets. And like one of the skill sets is talking. And if you’re a talking person, and like you could be a comedian, you could be a lawyer, you could be a person at the bar who doesn’t get kicked out as often as they should, because you tell great stories. Like you’re in a John Cassavetes film. You know, there’s like so many jobs that talking could be, but I feel like, talking is one of the things I’m good at and I think it’s been a real struggle to accept that that’s what I am because I feel like there’s more value in being the thing you have to try harder at, which, that doesn’t make sense. I know it doesn’t.

Well, of course, one of the rationales that Babs, if I can call her Babs. One of her rationales for thinking of herself as a director, actor and not as a singer is probably because she doesn’t tour often. And of course, now you’re touring. Segue! What did we get wrong about Segways? Anyhow? Segues.

I think it was the guy who bought the company but hadn’t invented them drove his into a ravine? There’s something to it. Yeah.

— James William “Jimi” Heselden OBE, was an English businessman who bought Segway Inc. in 2009, and died the following year after falling from a cliff while riding his own Segway PT.

We definitely got that wrong. But you’ve now began touring and that’s part of the reason that I’m privileged to have you on my podcast is you’re touring with the comedian and writer Jamie Loftus. What have you learned about comedy hanging out with Jamie?

Oh my gosh. Wow. I feel like what I’ve learned, the main thing is that I’m just like, I’ve been kind of thinking about comedy for a lot of my life, but not nearly as much as other people. I don’t know it’s like, first of all, a reminder of just how big and deep that world is and how many ways there are to think about getting a laugh or like, going about doing what you want to do. I mean, I just like, what I love about her work and what I was initially, what made me so excited initially about reaching out and talking about doing kind of live performance stuff together. Was that I, last August I saw her one woman show Mrs. Joey Chestnut America USA, which is like, just this like, dreamlike performance art show that is very funny, very off the wall like very, like I think extremely accessible, because it’s just really silly. Like I think most of her work is like silly in some kind of a way that feels really great to me. And then like, the sort of the like visual language of it over time, you’re like, I don’t know why this makes sense to me. But like, there’s some way in which this makes perfect dramatic sense, what’s happening, and then it culminates in some kind of like a body thing. Or like, you know, she has to sit there and eat 20 hotdogs because that’s just like the dramatic balance of the play. She just has to do it. And I don’t know. It’s been such an amazing joy to just kind of have now done like a few different shows with her. Where like, we know in a general way what we’re gonna do out there, but we also are just like, figuring it out, like fairly close to the event itself. What is the conceit? What are we playing with in terms of the themes or the images that we’re working with? And it’s something where when we do shows where we’re kind of talking to each other or doing kind of character stuff, it’s just like, we have a sense of where we’re starting from and where we want to end up, but the rest we just kind of improvise out there and I feel like she’s showing me her world! And it feels so lucky to me. I feel like the most normal I can possibly feel when I’m like doing something gross onstage with her and when I’m doing normal stuff, I’m just like, is this right? Is this it? Am I doing this right? This can’t be right.

You’re probably eating a lot more hot dogs now than you needed before.

I am yeah, I actually I was reorganizing my refrigerator and I have an entire hot dog condiment area. And that’s just my life now. And I’m happy about it.

Just like they talk about how reality TV can never be real because once you introduce the cameras, it changes the performance. The same is probably, well it’s definitely true with this, because recording a podcast, you’re just imagining the listeners out there. But when you do a tour, you do the live show. Everything changes because you’re now doing the podcast in front of — it becomes an interactive thing when you have 200 or 500 people in front of you.

Yeah, yeah. Yeah! I’m curious about your thoughts on this, but I feel like I would rather have 500 actual people in front of me than like a theoretical untold number of people, or like unseeable, unimaginable number of people. Because it’s just like, I don’t know, to me, there’s something. I definitely did some theater when I was younger and I remember getting it and getting why it was great. And then me kind of, you know, many of us realize that at one point and then move on and kind of forget about it, but it’s like we’re living in such an era of, everything can be recorded. Like, most things are recorded. And so the idea like one of the things people ask a lot about this tour is like, oh, so like, Are you recording them, and you’re gonna release them as live episodes? Which is, you know, a very reasonable thing to do that a lot of podcasts do and it certainly cuts down on work, but I also feel like I’m like no, I feel like these are like, these like special things. They happen once and you’re there or you’re not and just the sort of the way it feels to have like, I don’t know, it’s just like, the more I think about it, the more I feel like it’s one of the most wonderful things about people, that it’s like, well, what did the humans do? And it’s like, OK, well, sometimes at night, right? They go home, and then they leave the house again, in the dark, to go to a big building to all sit quietly together, and stare. And all the people stare at like a couple of people at the front of the room. And then they just wait for the people to say things that will make them laugh together and then that’s what they do. They love it.

That’s really kind of hit on the the crux of the paradox of what’s going on in comedy right now. Where people are complaining. And it’s because for so many decades, comedy was just this thing that existed as a temporary or ephemeral thing. You went, you saw it, and it was gone. Once you started recording it and putting it through the internet, it no longer became this thing that was just for that audience at that time. And so anyone else viewing it takes it out of context. And they take what they want out of it when they weren’t even there. They weren’t part of the thing.

Right? Right. Right. Because it’s like the audience is like doing a job. It’s part of the orchestra or something.

They’re in real-time approving or disapproving of what’s happening. They’re the ones judging whether to cancel it or not. Not you watching it on Netflix five years later. But I want to bring this on home by asking you about your other podcast, You Are Good. It’s a podcast about movies and feelings about movies. Are you waiting to do the episode about Forgetting Sarah Marshall? Because I know you have feelings about that movie.

Yeah, I mean, look. I will always be the second Sarah Marshall. And that’s fine. There’s actually so many Sarah Marshalls. There’s another Sarah Marshall in Portland who makes hot sauce, and I see her hot sauce around. Have yet to meet her. There was the first person under the age of one who received multiple organ transplants was a Sarah Marshall. So you know, we’re pretty proud of that. Yeah, it’s funny. Forgetting Sarah Marshall is a movie that I haven’t seen since it came out. I walked out thinking it’s pretty good. It was pretty good. But I’ve always felt like you know, I’ve always felt like Jason Segel, just like — I would just like to have a sit down with him. I don’t have anything mean to say. I just want to be like Jason, Why of all names?

I use always use my middle initial professionally for that very reason. And even then, I’ve since found one other Sean L. McCarthy, who’s a freelance journalist in entertainment. But he’s younger than me, so I’m sorry, other Sean McCarthy. But seeing what that movie did to Russell Brand. And now that Russell Brand has become his own you’re wrong about podcaster. Does that make him officially your nemesis?

I am like seven things behind on Russell Brand news. What’s he been up to? Is he anti-vaxx? I feel like that’s a good chance.

I mean, his brand, Russell Brand’s brand now is questioning everything. Which I feel is trying to like stomp on your turf, which, as someone who only became famous in America because of Forgetting Sarah Marshall, feels like a double whammy.

Yeah! The man cannot get off my coattails. It’s rather embarrassing. Yeah, I mean, it’s actually funny to me like how little it comes up with like people mentioning the movie to me. The only time that this movie comes up in my life is when I’m paying for something with a credit card, four times a year, someone will be like, Oh, your name is the same as a movie. But I feel I’ve been luckier than I expected in establishing a career where people are like, I know that you are a different one.

That’s pleasing to hear that it’s not bedeviling you. Especially since it is in your URL. You have explicitly acknowledged it. Every once in a while, when the term McCarthyism gets thrown around, I have to go: No relation!. Or Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy? No relation!

And that Mary McCarthy? I don’t know. She’s all right.

The only one I acknowledge is Charlie McCarthy, the ventriloquist dummy.

Candice Bergen’s brother.

Yeah. We’re related. Well, Sarah Marshall, thank you so much for spending some time with me and I look forward to seeing you and Jamie when you get to Brooklyn, and have fun on your tour.

Thank you so much. I can’t wait to see you and be gross in front of you. It’s my life’s dream.

Leave a comment